[ad_1]

Videoconferencing, podcasts, and webinars surged in popularity during the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 as remote work became part of the new normal. With the pandemic now in the rearview mirror, video communications techniques have shown no sign of slowing down.

What’s been amusing to me is that despite the pervasiveness of video communications, how unflattering we often appear on camera using underpowered, low-resolution webcams get too little attention. Poor lighting, mainly when using video calls from home, is undoubtedly a big problem. Sub-HD resolution webcams built into most, even high-end, laptops don’t help.

Without the professional assets available in a professional television studio, politicians, celebrities, and industry experts often look ghastly when being interviewed remotely from their homes.

Routine videoconferencing calls from home are especially vulnerable to an “amateur hour” look and feel, particularly during a formal presentation where wandering eye gaze (e.g., not looking directly into the webcam) can distract the viewer.

The location of the webcam is responsible for this unwelcome effect because the camera is generally integrated at the top of the laptop panel or on a separate stand that is difficult to place in front of a desktop display.

Because typical videoconferencing using a desktop or laptop PC doesn’t have proper teleprompter functionality, which is complex, bulky, and expensive, it’s nearly impossible to read speaker notes without avoiding the annoying phenomenon of a horrible webcam angle that stares up or down your nose.

Are there any quick ways to fix the eye gaze problem?

There are a few ways to mitigate this problem in a typical desktop or laptop home setup. However, these approaches are strictly gimmicky and don’t eliminate the problem.

A couple of companies provide tiny external webcams, often equipped without an integrated microphone, to reduce the device’s size and allow placement in the center of your screen, in front of any text material or the viewing window itself of the video app you are using.

These cameras use a thin wire draped and clipped to the top of the display. In this way, you look directly into the webcam and can see most, though not all, of the presentation or text material you are presenting.

Still, another method is using a clear piece of acrylic plastic that allows you to mount nearly any webcam and hook it to the top of the display so that the webcam suspends itself in front of the display’s center point.

The advantage of this approach is that it frees you to use your preferred webcam. The downside is that the size of the webcam and the acrylic plastic apparatus often obscures a good portion of the screen, making it less useful as a teleprompter alternative.

Down the road, we may see laptop and PC displays with integrated webcams behind the LCD panel, which are invisible to the user. While this is an ideal fix for the problem I’ve described above, the downside is that the cost of these specialty displays will be very high, which most manufacturers will be reticent to offer due to the price elasticity implications.

AI can fix eye contact issues conveniently and cost-effectively.

The idea of using artificial intelligence to mitigate or eliminate eye contact during videoconference calls is not new. When done correctly, AI can eliminate the need to purchase expensive teleprompting equipment that television studios use or resort to some of the gimmicky methods I’ve described above.

The challenge with employing AI to perform eye contact corrections on the fly (live) or even in a recorded scenario is that it requires processor horsepower to do much of the heavy lifting.

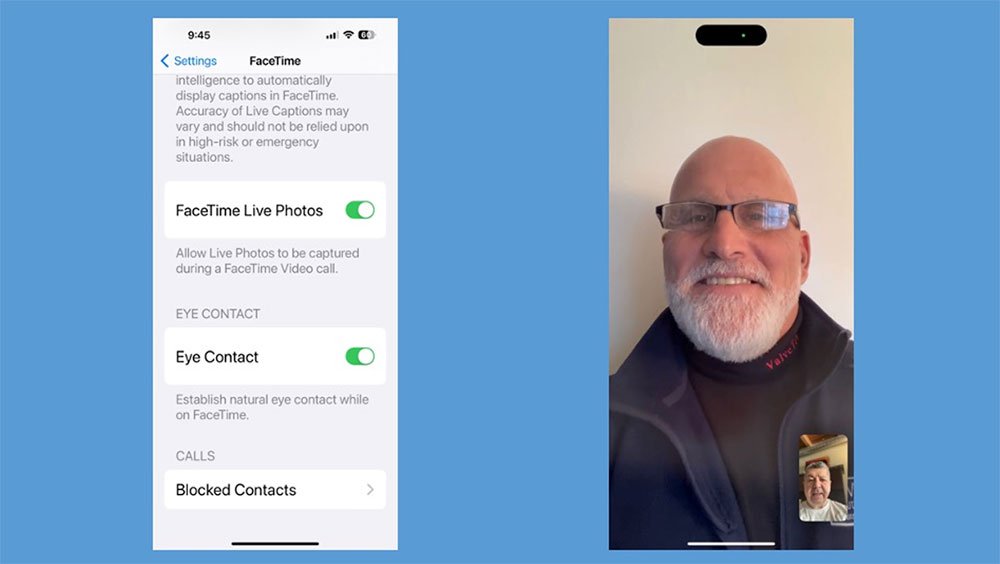

Apple Silicon has had this integrated capability for a few years with its iPhone chips. Not many users know that Apple’s FaceTime app has eye contact correction (which can be turned off), which ensures that your eye stare is focused on the middle of the screen, regardless of the orientation of the iPhone.

Eye Contact setting in Apple’s FaceTime app

Microsoft has also joined the AI party to fix eye contact issues. Last year, it announced that it would add eye contact solution capability to Windows 11 by leveraging the power of Qualcomm’s Arm solutions and taking advantage of neural processing unit (NPU) silicon to enhance video and audio in meetings — including subject framing, background noise suppression, and background blur.

Many of these features have already been available on Microsoft’s Surface Pro X device, which uses an Arm chip. Still, Microsoft will broadly deploy this functionality on more compatible models from major PC OEMs this year.

Nvidia Broadcast With Eye Contact

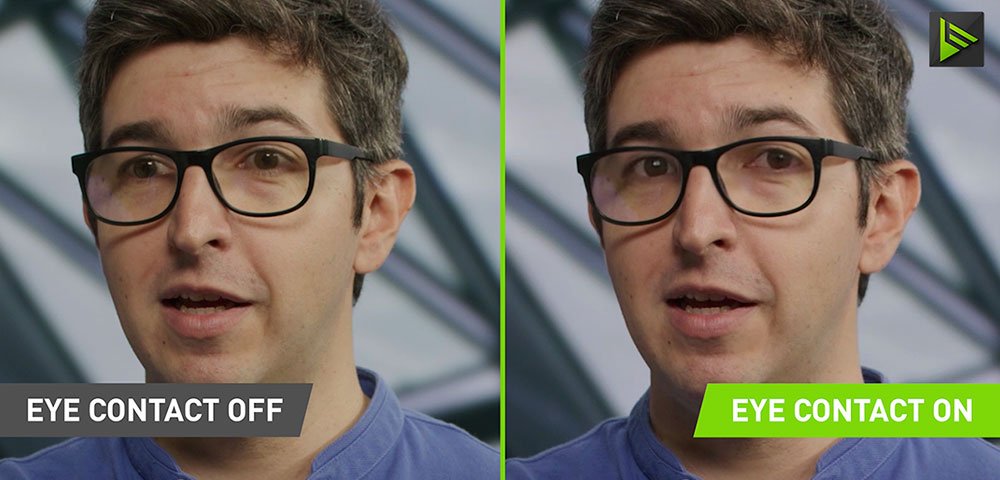

Nvidia’s Broadcast app, which works on a wide range of Nvidia external graphics cards, is a robust AI tool that improves video calls and communications on x86-based PCs. Last week, Nvidia enhanced the utility in version 1.4 to support its implementation of Eye Contact, making it appear that the subject within the video is directly viewing the camera.

The new Eye Contact effect adjusts the eyes of the speaker to reproduce eye contact with the camera. This capability is achieved using the AI horsepower in Nvidia’s GPUs to estimate and align gaze precisely.

The new Eye Contact effect in Nvidia Broadcast 1.4 moves the eyes of the speaker to simulate eye contact with the camera. | Image Credit: Nvidia

The advantage of Nvidia’s approach is the capability is not confined to a single videoconferencing platform or app. Apple only supports its eye contact correction capability using iPhone’s FaceTime app. However, I wouldn’t be surprised if Apple extends this capability to macOS users later this year in conjunction with its Continuity Camera capability.

In addition, Nvidia Broadcast provides Vignette functionality comparable to what many Instagram app users experience. This way, Nvidia Broadcast can generate an understated background blur to get an AI-simulated hazy visual on your webcam, immediately enhancing visual quality.

Substituting background images on videoconference calls is nothing new. Still, Nvidia’s approach will presumably offer better quality as it harnesses the power of its graphics cards, which are optimized for video content creation and gaming.

Closing Thoughts

The eye contact feature in Nvidia’s Broadcast app is currently in beta form and is not suitable for deployment yet. Like any beta feature, it will suffer from inevitable glitches, and we should delay formal judgment of its quality until the production version is made available.

Moreover, Nvidia Broadcast is not just a run-of-the-mill app but an open SDK with features that can be integrated into third-party apps. That opens up interesting new potential for third-party applications to directly leverage the functionality in Nvidia Broadcast.

Despite that, I’m amazed by some of the adverse reaction that has appeared over the last few years around the prospect of using AI to correct eye contact. Some tech analysts have used phrases like the “creepiness factor” to categorize this feature in the most unappealing manner possible.

Indeed, the capability will inspire many, perhaps deserved, jokes if the after-effect looks unnatural and artificial. However, the creepy designation seems over the top and disingenuous. One could make the same insinuation around using makeup or deploying enhanced tools that correct audio deficiencies during a video call. Apps like TikTok or Instagram would not exist without filters, which create far creepier images, in my view.

Like it or not, videoconferencing has survived as one of the positive outcomes of the post-pandemic world. Utilizing technology that facilitates more productive, compelling, and impactful video calls is something we should welcome, not scorn.

As someone who produces a weekly video podcast and recognizes the potential of eliminating or even reducing eye gaze, which could, in turn, introduce teleprompter-like advantages, I look forward to testing this much-needed capability over the next coming weeks.

[ad_2]

Source link